New details have emerged about the damage a tornado dealt to Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska in 2017, a storm that left only one the U.S. Air Force’s E-4B Nightwatch airborne command centers operational for three months. The incident only further highlights the service’s push to modernize the vital nuclear command and control aircraft, a still evolving plan that could eventually lead to a new aircraft that would also replace the C-32A “Air Force Two” executive transports charged with carrying the Vice President and other senior officials and U.S. Navy’s E-6B Mercury airborne command posts.

On June 16, 2017, an EF-1 tornado – defined as a cyclone producing winds between 86 and 110 miles per hour and capable of flipping mobile homes and breaking windows – touched down at Offut, causing almost $20 million in damage in total. This included a more than $8 million bill just to repair both of the E-4Bs, also known as National Airborne Operations Centers (NAOC), which were at the base at the time, according to the Omaha World-Herald. The Air Force has four of the aircraft in total, and, as we reported at the time, Boeing was overhauling a third aircraft at its depot in San Antonio, Texas, leaving the fourth as the only one on active duty at a still undisclosed base.

“It was almost the worst possible path,” Colonel Dave Norton, head of the 55th Wing Mission Support Group told the World-Herald. “It’s remarkable that no one was hurt.”

The Air Force’s highly specialized 55th Wing is the service’s main unit at the base, which is also home to U.S. Strategic Command, the Pentagon’s headquarters in charge of America’s nuclear arsenal. Squadrons assigned to the 55th fly the E-4B, as well as various RC-135 spy planes, the OC-135 Open Skies surveillance aircraft, and the WC-135 Constant Phoenix nuclear reconnaissance platform.

The Nightwatch’s primary mission is to safely carry the National Command Authorities and enable to them to order a nuclear strike or other major military operation in response to a crisis. They are also available to assist the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during major natural disasters, to transport the Secretary of Defense and their staff during overseas trips, and to shadow the VC-25A “Air Force One” carrying the President of the United States during foreign visits. In each case, the aircraft is on call to provide important command and control and communications relay functions.

Though thankfully the base’s staff escaped the incident unharmed, the Wing’s aircraft, including eight RC-135s, were not so lucky. The two NAOC aircraft found themselves in a particularly bad situation.

Initially fearing a hailstorm, the 55th’s personnel had moved the aircraft into a hangar. Though the shelter was not big enough to fully cover the huge E-4Bs, which are heavily modified Boeing 747-200 airliners, this would have at least protected the cockpit, wings, engines, and various randomes and antennas arrayed along the aircrafts’ fuselage.

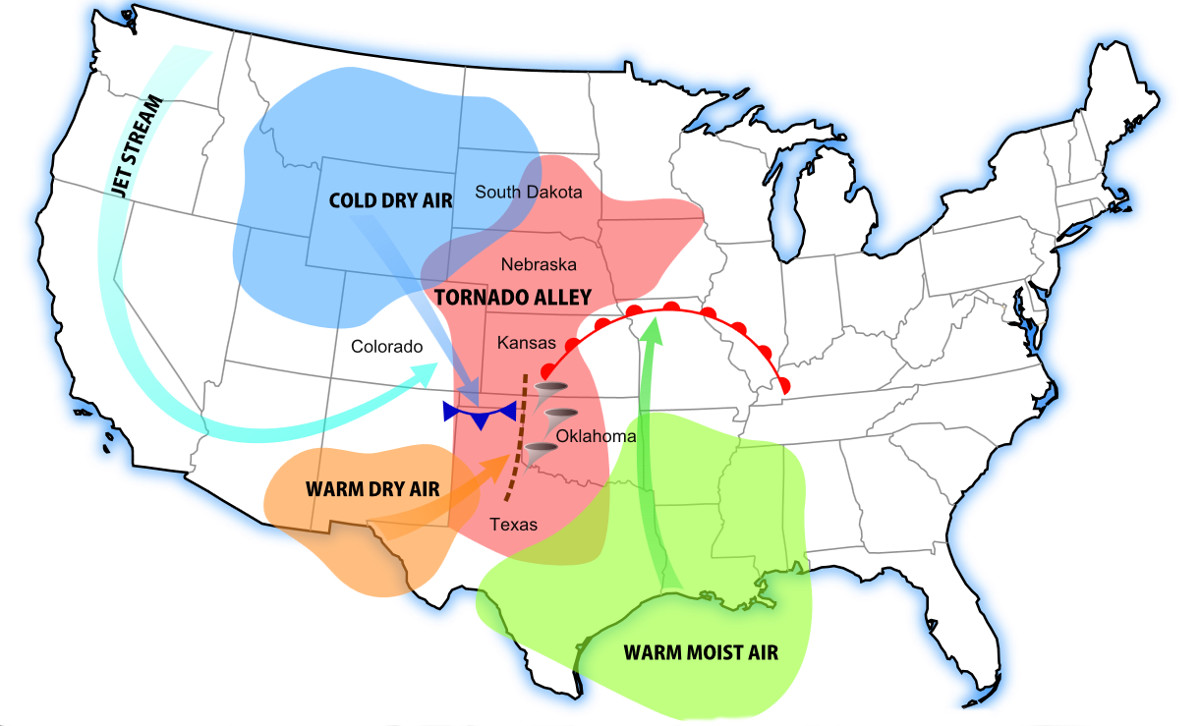

It’s worth noting that despite being home to these aircraft, there is no hangar at Offutt big enough to fully shield them from this kind of storm. The base is well within what is known as “Tornado Alley” and routinely runs Tornado National Disaster Rehearsal Exercises (NDRE). To fully protect the E-4s and other specialized planes from any damage, they would likely have had to evacuate to another base, a procedure that requires some amount of time and planning and isn’t always practical, as is obvious from this particular incident.

When the tornado hit in June 2017, the wind turned the planes’ exposed tails into giant sails, pushing the more than 350,000 pound aircraft around with ease, smacking them into other objects inside the hangar. It was also enough to yank open the already ajar 30,000 pound hangar, exposing everything to the elements outside.

“The biggest thing was the noise,” Master Sergeant Ken Parker, a member of the 595th Aircraft Maintenance Squadron who was the superintendent on duty in charge of the facilities at the time, told the World-Herald. “It was deafening.”

The storm drove one of the four engine jets into a maintenance stand, punching a hole into its nose. One of the planes ended up leaking fuel from a wing tank, creating a hazardous situation that base firefighters were thankfully able to contain.

We still don’t know the full extent of the damage, but apparently it could have been even worse. Master Sergeant Parker, along with Technical Sergeants Olivia Fernandez and Walter Scott, all received commendation medals for their quick thinking before the tornado hit. They risked their lives, ran from where they had taken shelter in a nearby hallway, and removed retaining pins that locked the nose gear in place on both E-4Bs, before returning to safety.

“If (the nose gear) wouldn’t have been allowed to move freely, it could have collapsed,” Parker explained. “The team went in the hangar and tried to save the airplane as best we could.”

The damage still sidelined the planes for 11 weeks. The 595th Maintenance Squadron won Air Force Global Strike Command’s annual “Maintenance Effectiveness Award” for their efforts to get those planes, as well as the storm-battered RC-135s, back in service as quickly as possible.

Though the Air Force clearly did an impressive job in getting the aircraft flying again, the incident only further underscores the increasing difficulties in sustaining the small and aging E-4B fleet. Boeing introduced its 747-200 in the 1970s and has not produced the aircraft in decades. At the same time, airlines have already divested these earlier Jumbo Jets as operating costs and maintenance demands have steadily increased over the years and many have stopped flying 747-type planes altogether.

The Air Force is also facing the prospect of needing to replace four Boeing 757 airliner-based C-32A Air Force Two specialized transport planes. These aircraft, which though far less capable than the 747-200-based VC-25A Air Force Ones that shuttle the President around, still have significant command and control capabilities and are another component in the U.S. government’s aforementioned continuity protocols.

On top of that, the service has been looking for ways to collaborate with the U.S. Navy, which is already developing a plan to replace its 16 E-6B Mercury nuclear command and control planes, which use a heavily modified Boeing 707 airliner airframe, even though those aircraft will remain in service until at least 2038. The planes share some functionality with the E-4Bs, notably in their ability to coordinate the release of America’s nuclear weapons for strikes during a crisis.

As we at The War Zone have already noted in the past, having a single platform capable of performing these different roles could greatly improve the flexibility of critical nuclear and other executive command and control functions compared to the existing arrangement. A common, more modern airframe would also help reduce operating and maintenance costs.

The Navy already flies the Boeing 737-based P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol plane and the Air Force is hoping to begin receiving Boeing 767-based KC-46 aerial tankers soon, both of which could serve as potential base for a new command and control aircraft. The Chicago-headquartered planemaker’s 777 and 787 aircraft might options, as well, but neither is in military service and it could cost a significant amount to develop and implement a suitable conversion plan for either type. In addition, they are larger and could require more extensive facilities to support them on the ground, further raising costs.

A stretched 737-based aircraft would probably still be too small to adequately fill the role of the existing E-4B, C-32A, and E-6B aircraft, potentially making a 767-based platform an even more attractive choice. The Air Force has already demonstrated that the KC-46 might be able to withstand the electromagnetic pulses from a nuclear weapon going off in its existing configuration, which would be a critical capability for any new airborne command and control aircraft.

Right now, the Air Force and the Navy are still developing the full requirements and time frame for when a common aircraft might begin to enter service. In President Donald Trump’s first defense budget request, for the 2018 fiscal year, there were plans to set at least $6 million aside to look study options to replace the E-4Bs and the C-32As with a single new platform. There was another, separate multi-million dollar proposal to examine the possibility of finding one type of aircraft to perform the functions of both the E-4B and the E-6B, which the Air Force has begun tentatively referring to as the Survivable Airborne Operations Center (SAOC).

The Trump Administration’s second proposed defense budget, covering the 2019 fiscal cycle, asks for nearly $18 million to continue both of those so-called “analysis of alternatives.” It does not indicate when either the Air Force or the Navy might arrive at a final decision about how to proceed, or how long it might take after that for them to move through the necessary contracting processes to procure any actual planes.

Though this is still a relatively small amount of funding for this project, the Air Force’s budget outlay indicates that the service understands that it needs to move fast if it wants to find a common platform. The budget proposal says the service will ask for nearly $20 million for the SAOC alone in the 2020 fiscal year and then more than $100 million in each of the next three budget cycles.

Money for the C-32A replacement project does remain relatively level during that same period, but with a note that the Air Force will continue to “explore commonality and standardization of subsystems and airframes” with the SAOC aircraft. The service could potentially fold the two funding streams together if it more formally consolidates the development and procurement plans.

The primary goal appears to be to replace all three aircraft no later than 2040. A common platform could easily enter service incrementally and replace the older E-4B and C-32A aircraft first, with additional planes then arriving to take the place of the newer E-6Bs.

In the meantime, these aircraft will have to continue to perform their various critical functions. The C-32As are in the midst of a broad upgrade program that should extend their service beyond the aircraft’s original 25-year service life, which they will hit in 2023.

The Air Force and the Navy are also continuing to move ahead with scheduled upgrades to the E-6Bs, which will improve their data sharing capacity, command and control capabilities, and additional defenses against both electronic warfare and cyber attacks. In October 2017, Lockheed Martin and Rockwell Collins both received major contracts – more than $80 and $76 million respectively – to develop prototypes of these new mission systems as part of the Airborne Launch Control System Replacement (ALCS-R) program. The Air Force is running the project and will eventually select a single contractor to produce and install the equipment.

But “we’re only 20 years from 2038, so if you’re going to build large aircraft with huge command and control [requirements], you have to start thinking about those things right now,” U.S. Air Force General John Hyten, head of STRATCOM, head already said in March 2017. “That’s what the Navy is starting to do, I’ve requested they start looking at defining what comes next.”

Those command and control requirements, which are essential to the U.S. military’s nuclear deterrent capabilities and the United States’ ability to respond to catastrophic scenarios of all types, only appear to be increasingly important. Increased tensions with North Korea have raised concerns about a potential nuclear strike on the United States to their highest point in decades and Russia recently announced that it is working on a slew of strategic super weapons primarily aimed at breaking through any future U.S. missile defenses.

With the two services already looking into what it might take to get a single plane that meets their various needs, we could easily start seeing proposals from Boeing or other manufacturers sooner rather than later.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com